Fusion energy is a form of energy produced when light atomic nuclei combine to form a heavier nucleus. This process releases large amounts of energy because a small fraction of the mass of the original nuclei is converted into energy, as described by Einstein’s equation E = mc^2. Fusion is the same fundamental process that powers the Sun and other stars. On Earth, the most practical fusion reaction involves two isotopes of hydrogen: deuterium and tritium. When these nuclei fuse, they form helium, release a high-energy neutron, and produce a tremendous amount of heat.

To make fusion occur, three conditions must be met simultaneously: extremely high temperature, sufficient particle density, and adequate confinement time. The temperature must reach tens of millions of degrees Celsius so that the positively charged nuclei have enough energy to overcome their natural electrostatic repulsion. At these temperatures, matter exists as plasma, a hot, ionized gas composed of free electrons and atomic nuclei. Because no solid material can contain plasma at such temperatures, special techniques are required to confine and control it.

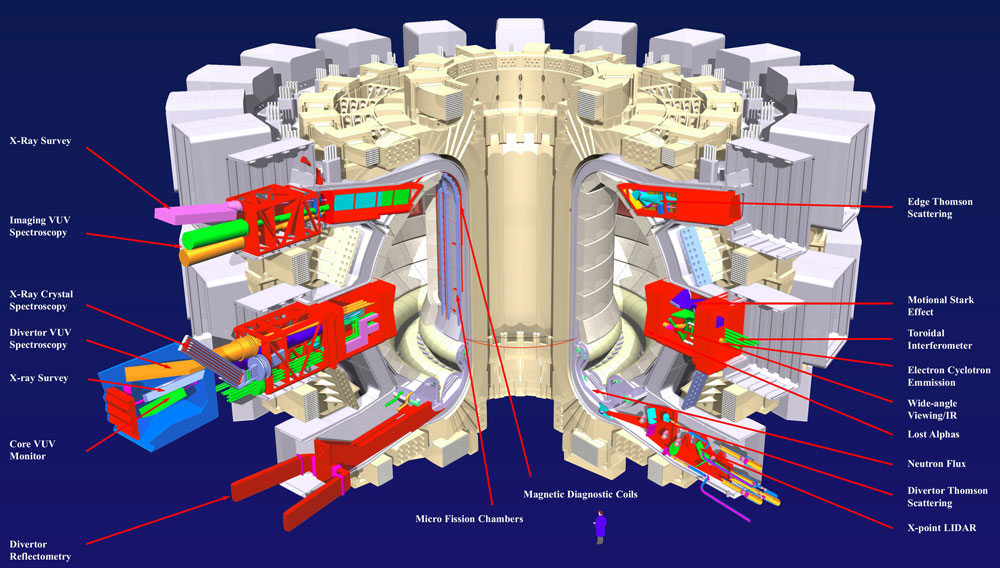

The most advanced method for collecting and controlling fusion energy is magnetic confinement. In devices such as tokamaks and stellarators, powerful magnetic fields are used to trap plasma in a toroidal (doughnut-shaped) chamber. Charged particles spiral along magnetic field lines, preventing them from touching the reactor walls. External systems heat the plasma using electric currents, microwave radiation, or neutral particle beams. Sophisticated control systems continuously adjust the magnetic fields to maintain stability, suppress turbulence, and keep the plasma confined long enough for fusion reactions to occur.

Another major approach is inertial confinement fusion. In this method, tiny pellets containing deuterium and tritium are rapidly compressed using intense laser beams or particle beams. The outer layer of the pellet explodes outward, forcing the inner material inward and briefly creating the extreme temperature and pressure needed for fusion. The confinement is provided by the inertia of the fuel itself, but only for a fraction of a second. Although the duration is short, the density is extremely high, allowing fusion reactions to take place.

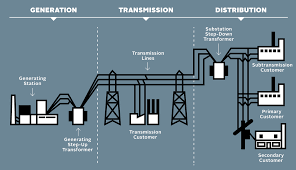

Collecting the energy from fusion involves capturing the heat and particles produced by the reactions. In deuterium–tritium fusion, most of the energy is carried by fast neutrons. These neutrons escape the magnetic fields and strike a surrounding blanket made of special materials. Their kinetic energy is converted into heat, which is then transferred to a coolant, such as water, helium, or molten salts. This heat can be used to produce steam, drive turbines, and generate electricity, much like in conventional power plants. The blanket can also be designed to breed tritium from lithium, replenishing the reactor’s fuel supply.

Controlling fusion safely and efficiently requires advanced diagnostics, real-time monitoring, and automated feedback systems. While significant engineering challenges remain, successful fusion would provide a nearly limitless, low-carbon energy source with minimal long-lived radioactive waste, making it a promising option for future global energy needs.

Powering homes and businesses with fusion energy offers significant benefits that could transform the global energy system. Fusion has the potential to provide a nearly limitless and reliable source of electricity because its primary fuels—hydrogen isotopes—are abundant. Deuterium can be extracted from seawater, and lithium, used to produce tritium in fusion reactors, is widely available. This means fusion could supply energy for millions of households and businesses for centuries without the fuel shortages associated with fossil fuels.

One of the most important advantages of fusion power is its environmental impact. Fusion produces no carbon dioxide during operation, making it a powerful tool for reducing greenhouse gas emissions and combating climate change. Unlike coal, oil, or natural gas, fusion does not release air pollutants that contribute to smog or respiratory illness. It also generates far less long-lived radioactive waste than traditional nuclear fission, and the waste it does produce becomes safe much more quickly, reducing long-term storage concerns.

Fusion energy is also inherently safe. Fusion reactions require extremely precise conditions of temperature and pressure to continue. If a system malfunctions or loses power, the reaction naturally shuts down rather than running out of control. This eliminates the risk of catastrophic meltdowns and large-scale radiation releases, making fusion power plants well suited for use near population centers that supply homes and commercial districts.

For homes and businesses, fusion promises a stable and continuous power supply. Unlike solar and wind energy, fusion is not dependent on weather or time of day. This reliability could reduce the need for large-scale energy storage systems and help stabilize electrical grids. Businesses, particularly those reliant on constant power such as data centers, hospitals, and manufacturing facilities, would benefit from fewer outages and more predictable energy costs.

Finally, widespread fusion power could lower long-term energy costs and strengthen energy independence. By reducing reliance on imported fuels, communities and nations could achieve greater economic stability while providing clean, dependable electricity to homes and businesses alike.

Fusion energy could power transportation devices by providing a highly efficient, long-lasting source of electricity or heat that can be converted into usable propulsion. Because fusion releases enormous amounts of energy from very small amounts of fuel, it could enable vehicles to operate for long periods without frequent refueling, transforming how transportation systems are designed and used.

In the near term, fusion would most likely power transportation indirectly. Large fusion power plants could generate electricity for charging electric cars, buses, trucks, and trains. With a stable, carbon-free power source, electric transportation networks could expand without increasing emissions, making road and rail travel cleaner and more reliable. Ports and airports could also use fusion-generated electricity to power cargo handling equipment and ground operations.

In the longer term, compact fusion reactors could potentially be used directly in large transportation systems. Ships and submarines could benefit first, as they have space for heavy shielding and reactors. Fusion-powered vessels could operate for years without refueling, reducing costs and eliminating emissions at sea. Advanced fusion systems might also power long-distance trains or even aircraft by producing electricity for electric propulsion or by generating high-energy plasma for advanced engines.

Fusion could also enable new forms of space transportation. Fusion-based propulsion systems could provide continuous thrust with high efficiency, drastically reducing travel time to other planets and allowing deeper exploration of space. While major technical challenges remain, fusion energy holds the promise of cleaner, more efficient transportation across land, sea, air, and space.